Alfie & Me

For curious and compassionate nature lovers who seek to deepen their understanding of the intricate connections between humans and animals, Alfie & Me offers a beautifully woven narrative that explores the profound bond between a scruffy owlet and an insightful naturalist. Through the eyes of Alfie, this book reveals the mysteries of our relationship with the wild and inspires a vision for a more compassionate and connected world.

It will invite you to discover the beauty of nature through compelling storytelling and philosophical reflection, leading to a deeper appreciation of the natural world and a renewed sense of responsibility for its care.

With praise from esteemed voices like Scott Weidensaul, Frans de Waal, and Sy Montgomery, Alfie & Me provides an eloquent and urgent message, blending drama, wisdom, and insight to illuminate the twin truths of compassion and connection. Experience the transformation of seeing the world through Alfie’s eyes and embracing a more empathetic and connected approach to nature, as this masterful narrative guides you to a greater understanding of our place in the natural world and our role in its preservation.

What People Say About “Alfie & Me”

“This is a book about a foundling owl, and infinitely more. As it turns out, the universe and all its mysteries, our relationship with our wild kin and a better future for ourselves and the planet—all are reflected through the prism of an eight-inch ball of feathers named Alfie. Carl Safina has never been more eloquent, or more urgent. Alfie & Me is masterful.”

—Scott Weidensaul

Author of A World on the Wing: The Global Odyssey of Migratory Birds

“The rescue of a little screech owl brings Carl Safina the unexpected joy of companionship and propagation of the species, leading him to philosophize about humanity and how much we’re part of nature. A delightful read!”

—Frans de Waal

Author of Different: Gender Through the Eyes of a Primatologist

“Carl Safina has written a book of great wisdom and beauty, full of drama and insight. How right to choose an owl, symbol of learning, to help us see anew the twinned truths of compassion and connection—gifts our kind desperately needs to keep our world alive.”

—Sy Montgomery

Author of The Soul of an Octopus: A Surprising Exploration into the Wonder of Consciousness

Psst… introduce Alfie to the kiddos!

✨ Step Into the Magic of Owls in Our Yard! ✨

Meet Alfie, the Eastern Screech Owl, in Owls in Our Yard!—a children’s book by Carl Safina that will delight kids and grown-ups alike!

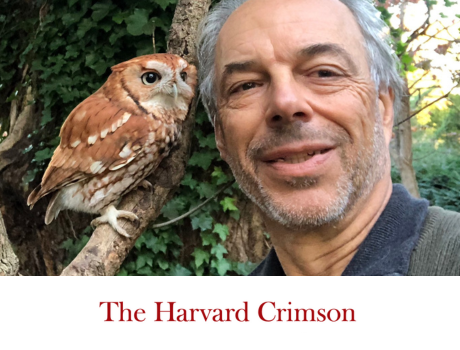

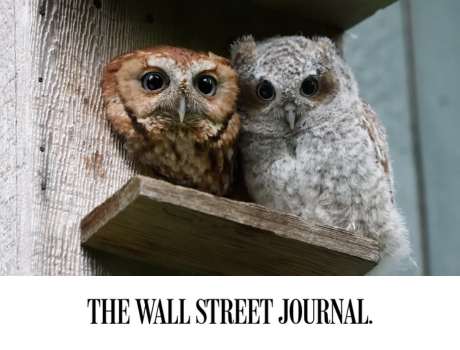

In the spring of 2019, ecologist Carl Safina and his wife, Patricia, took in little Alfie, a bedraggled Eastern Screech Owl chick who quickly became part of their family. With the Safinas’ care and expertise, the little owl grew, learned to hunt on her own, and eventually found her own family in a mate and chicks. As time passed, Carl realized that his bond with Alfie was greater than just saving her life—it offered wisdom, joy, and magic to him in return.

Owls in Our Yard! is a beautiful story filled with heartwarming photographs and Carl Safina’s warm narrative. It’s a celebration of the bond between humans and wildlife, perfect for sparking curiosity and joy in young readers and those young at heart.

Explore More

AUTHOR TALKS & INTERVIEWS

READ

READER TAKES

About Carl Safina

& The Safina Center

Carl Safina’s writing merges science, emotion, and ethics to examine human impact on nature. A MacArthur “genius” prize winner and founder of the Safina Center, he is also the first Endowed Professor for Nature and Humanity at Stony Brook University. His PBS series Saving the Ocean and writings in major publications showcase his deep nature connection. Safina’s ten books include Song for the Blue Ocean and Beyond Words. His latest is Alfie & Me. He lives on Long Island with his family and their feathered friends.

The Safina Center is a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting a deeper understanding of the natural world and fostering a meaningful connection between people and nature. Through research, writing, and media projects, the Center addresses critical environmental issues and inspires action to protect the planet. Founded by Carl Safina, the Center combines scientific insight with a compelling narrative to drive positive change for both wildlife and human communities.