The Comeback Bird

A review by Patricia Paladines and Carl Safina

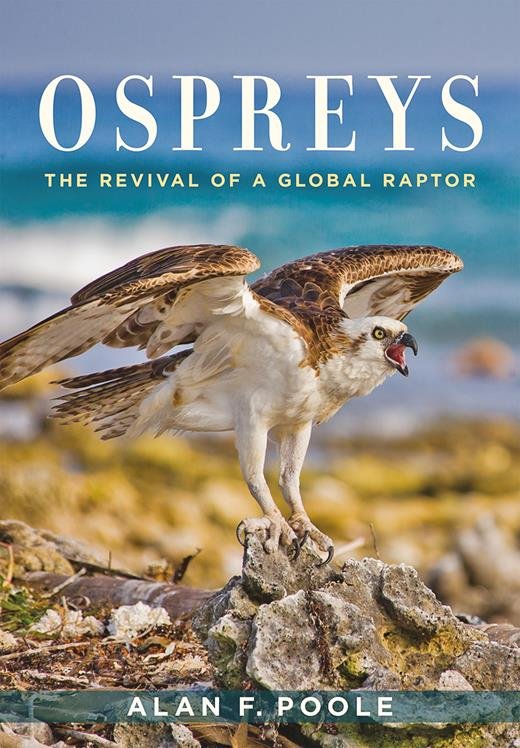

Ospreys: The Revival of a Global Raptor by Alan F. Poole

Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019

220 pages, hardcover ABA Sales–Buteo Books 14921

When it comes to us and Ospreys, it’s deep and personal. Around 1970, a neighbor took an adolescent Carl to a secret fishing spot on an eastern Long Island pond. He saw a huge stick nest, and from what he’d been reading he knew some things: it was an Osprey nest, abandoned, and Ospreys were nearly extinct. DDT and other pesticides, “elixirs of death” in Rachel Carson’s words, had wreaked their havoc. And they were all still very much in use. Carl couldn’t believe he’d just missed the existence of birds who could make a nest like that. To him, for him, what future could there be? All seemed lost.

But the worst of those pesticides were banned in the early 1970s and we watched Ospreys begin a long, slow, gathering recovery. The two of us didn’t meet until the mid-1990s when we both worked at a nature sanctuary. We got to know each other by taking walks to the bay, where we’d look for Ospreys. Nowadays, married, in March we usually take a special morning to seek out the first Osprey sighting of the year. And we usually have a bit of a contest about who’ll get the first glimpse. Ospreys have been, and remain, a big part of each of our lives and remain a touchstone of our life together. Patricia will always carry the memory of walking to get her Bachelor’s diploma at an outdoor graduation ceremony and having a vocalizing Osprey circling the proceedings, adding propitious uplift to a triumphal moment.

So we were delighted by the publication of Alan Poole’s deeply informed and superbly produced, Ospreys: The Revival of a Global Raptor. Poole tells the story of seeing his first Osprey when he was around 7 or 8 years old. One morning in the 1950s, shortly after dawn, Poole and his father had launched their canoe into a lake in the northeastern United States headed to a trout stream on the other side. Nearing their destination, he writes, “I barely noticed a large dark bird flying slowly along the shoreline as we approached, hovering at treetop level and moving on, then hovering again, long legs dangling. Suddenly the bird folded its wings and plunged, feet stretched forward, talons wide. The lake surface erupted in a shower of spray. Instantly I was awake and riveted. A few seconds later the long dark wings reached high, slowly the bird from the water, a flash of struggling silver in its grip.” Many of us who are passionate Osprey groupies can relate to that riveting first thrill of watching a “Fish Hawk” catch a meal.

This is Poole’s second book on Ospreys. The first, Ospreys: A Natural and Unnatural History, was published in 1989, after a nearly exterminated North American population had begun to rebound from the incautious use of aforementioned pesticides in the years following World War II. Poole admits getting quizzical looks from friends and colleagues who asked why was he bothering to write anew book on the same subject; wasn’t he bored with the species by now? How anyone might be bored with Ospreys eludes us, but thankfully Poole persisted with the task.

The resulting book can only deepen one’s passion as it enriches our amazement over how uniquely special these birds of prey really are. Within the pages of Ospreys: Revival of a Global Raptor, Poole shares the Osprey story that has emerged from three further decades of observations, research, and conservation efforts; one much more complex than what we understood in the 1980s.

Beautifully illustrated with stunning photographs and informative maps, the book takes us on a world tour of the current Osprey landscapes and global movements. “One hundred years ago we had only vague ideas of where our [migrating] Ospreys were headed,” writes Poole. “Even fifty years ago the picture was dim.” In the early days, metal leg bands that were reported, usually after a bird was found dead, had given researchers only a rough sketch of where the migrating Ospreys went in winter and the routes they took. Today the use of GPS transmitters strapped to the back of birds allows us to follow “Ospreys on the wing—hour-to-hour, sometimes minute-by-minute details that no one could have imagined before the invention of computer chips.” It has been a game changer from the times when researchers relied mainly on information collected from metal leg bands that were placed on young Ospreys before they fledged. Poole writes that “decades of data from band returns, together with the more recent flow of information from individuals tagged with satellite transmitters, have given us a clearer picture of Osprey migration patterns than is available for nearly any other bird on the planet. The broad patterns are now well established: about 90% of the world’s Ospreys are migrants, all coming out of the Northern Hemisphere breeding populations.” Winter in the northern latitudes finds most of these birds either in West Africa (western European nesters), or the northern half of South America (eastern North American nesters), with Mexico and other Central American countries hosting many of the migrants from western North America.

Satellite technology that came into use in the 1990s has illuminated the extraordinary annual migrations undertaken by tens of thousands of the North American and European birds to and from their tropical and subtropical wintering grounds. A cadre of dedicated researchers and “citizen scientists” have contributed enormous amounts of data that expands our knowledge of the Osprey’s life history. The global estimate of breeding Osprey pairs is now around 50,000, and an additional 25,000 to 30,000 unpaired birds, either too young to breed or unable to find a nest or mate, complete the estimated total world population. But the security of these numbers is tenuous, Poole says. “Eliminate the Ospreys of Sweden and the eastern half of North America... and you’ve lost about 70% of the world population.”

Poole complements his engaging modern-day narrative on Ospreys with various mini-biographical vignettes on individuals from around the world who have dedicated much of their lives to helping broaden the Osprey literature and implement conservation efforts. Among these Osprey devotees is Pertti Saurola, a legend in the world of Osprey research, who began observing Finland’s Ospreys systematically in the 1970s and now with a crew of more than 100 people monitors the country’s 1,300 Osprey nests. Rob Bierregaard is another vignette entry. He coined the term “Age of Silicon” in reference to the silicon chips that power computer devices, including the transmitters that Ospreys wear and the satellites that help track them.

Flavio Monti, a young Italian researcher based at the universities of Montpellier in France and Ferrara in Italy is also included in a vignette. His research takes an integrative approach for the understanding and conservation of Ospreys, with a focus on the Mediterranean population. By running DNA analyses from nearly 225 Ospreys (mostly from museum specimens but also some live birds) Monti shed light on the evolution of the species from its earliest origins in North America, some time before twelve to thirteen million years ago when a bird very much like the Osprey we see today was already widespread on the continent. His collaborative work relating to the Mediterranean Osprey has shown for the first time that the Mediterranean Osprey population does migrate, with some moving locally while others travel as far as West Africa. In mainland Italy Ospreys were wiped out in the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth century by shooting and nest robbing. But in the 1970s when many governments around the world expanded the circle of compassion beyond humanity, Ospreys gained protection in Italy. Monti led a successful effort to reestablish populations in Tuscany where Ospreys are now nesting for the first time in forty-five years.

Although the threats Ospreys faced in the last century have been significantly reduced, Poole says that Ospreys are not safe from all threats, and fish farms seem to be the most dangerous places for them today. One solution is to cover fish ponds with nets, but many of the smaller farms in Latin America and the Caribbean, where the birds seem to be most vulnerable, may not be able to afford to go that route. “Shotgun shells are cheaper than nets,” Poole explains. In other parts of the world, such as many Mediterranean countries, Ospreys continue to be shot for sport as they have been for generations. A significant cultural shift in the region may soon alleviate this threat as more young people, especially in Italy, France and Spain are expressing an increased reverence for wildlife and embarking on careers in wildlife sciences.

Alan Poole’s Ospreys: The Revival of a Global Raptor reengages us with a bird that very likely “greeted the first humans as they began to walk upright across the plains of Africa one to two million years ago, and later as our ancestors emigrated north in small bands into Europe and Asia and finally into North America fifteen to twenty millennia ago. No doubt Osprey nests would have dotted the landscapes around our ancestors’ camps in those northern regions, and people and Ospreys very likely hunted the same fertile waters... It’s a good bet that in early human societies Ospreys were part of nighttime conversations around campfires, woven into myth and culture, much as Ospreys enter the lives and conversations of people who live around them today.” This book is loaded with fascinating material to keep that age-old conversation going and deepen the passion of Osprey enthusiasts like ourselves who have been known to shed tears at the first sighting of a Fish Hawk in springtime.

There’s plenty to be concerned about nowadays. But one of the great solaces of our life is the resilience and recovery of these great birds, personally witnessed by so many of us and so uniquely well chronicled by Alan Poole. Ospreys are now much more abundant than we ever thought we’d see. For that, we are ever-thankful. On Long Island where we live, the sound and sight of them is common, and so very reassuring. Ospreys inspire us about what can happen, when all seems lost.